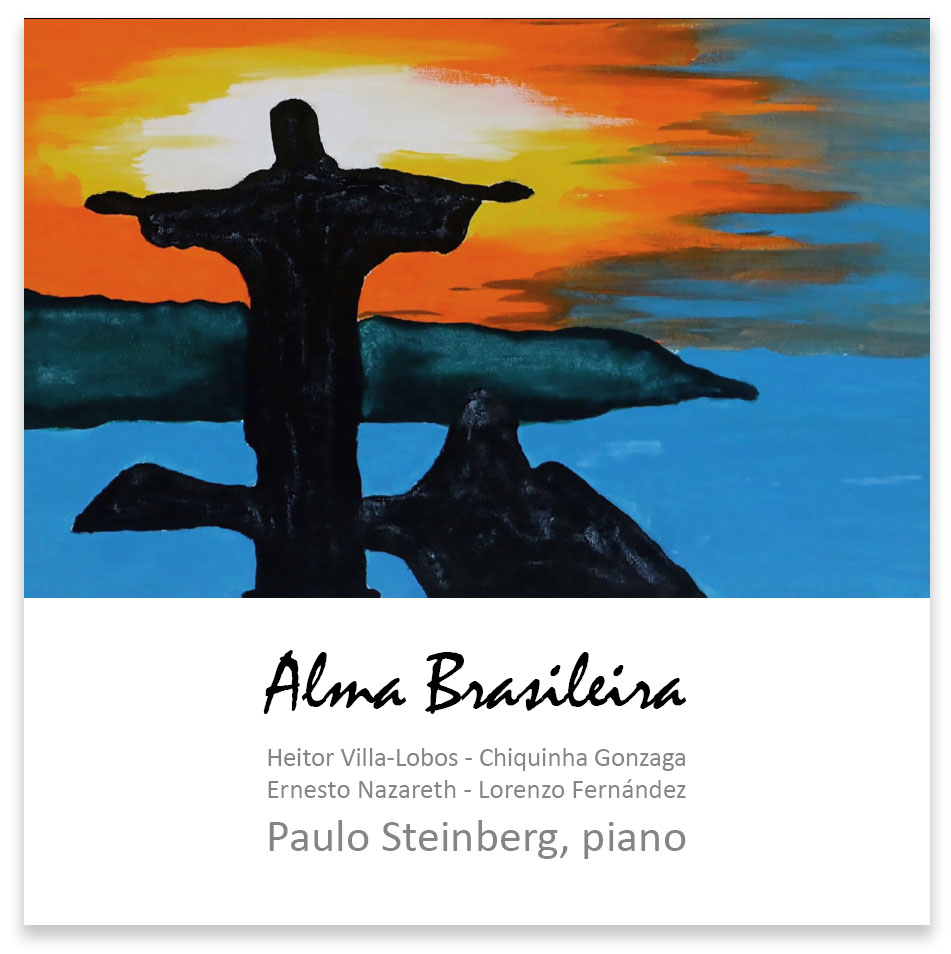

The CD-album Alma Brasileira, released in April 2017.

Album tracks:

Heitor Villa-Lobos

1. Choros No. 5: Alma Brasileira (Brazilian Soul) [4:55]

2. From Cirandas: Terezinha de Jesus [2:04]

3. From Cirandas: Senhora Dona Sancha [1:26]

4. From Cirandas: A Condessa (The Countess) [2:53]

5. From A Prole do Bebê No. 1: O Polichinelo (Clown) [1:39]

6. Guia Prático Album 6: Sonho de uma Criança (A Child’s Dream) [1:44]

7. Guia Prático Album 6: O Corcunda (The Hunchback) [0:57]

8. Guia Prático Album 6: O Caranguejo (Crab) [1:15]

9. Guia Prático Album 6: A Pombinha Voou (The Little Dove Flew Away) [1:49]

10. Guia Prático Album 6: Vamos atrás da Serra, oh Calunga! (Let’s Go Behind the

Mountain, oh Calunga!) [1:12]

11. Ciclo Brasileiro: Plantio do Caboclo (Native Planting Song) [4:45]

12. Ciclo Brasileiro: Impressões Seresteiras (Minstrel Impressions) [6:26]

13. Ciclo Brasileiro: Festa no Sertão (Sertão Festival) [5:09]

14. Ciclo Brasileiro: Dança do Índio Branco (Dance of the White Indian) [3:41]

Chiquinha Gonzaga

15. Lua Branca (White Moon) [2:05]

16. Gaúcho – Corta-Jaca [1:48]

17. Annita – Polka [1:43]

Ernesto Nazareth

18. Odeon – Tango Brasileiro [2:51]

19. Brejeiro – Tango Brasileiro (Mischiveous) [1:51]

20. Apanhei-te, Cavaquinho – Choro (I’ve Caught You, Cavaquinho) [2:50]

Oscar Lorenzo Fernández

21. Suite Brasileira No. 2: Ponteio (Prelude) [1:20]

22. Suite Brasileira No. 2: Moda (Song) [2:09]

23. Suite Brasileira No. 2: Cateretê (Dance) [1:44]

About the music

The music of Brazil exploded onto the world scene in the late 1950s simultaneously, and not coincidentally, with a brilliant soccer team (led by Pelé) that helped create a vogue for everything Brazilian. This was the era of Tom Jobim, João Gilberto, Ipanema, samba and futebol. In the classical music world, of course, the roots go back much further in time. This album celebrates composers and works whose bridging of art and pop culture forever changed music history. Arguably the greatest composer born in all of Latin America, and certainly the region’s most prolific composer, Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887-1959) came of age in early-20th-century Rio. It was a time of foment in world politics, and many South American countries looked to their arts to help express a newfound nationalist fervor. The climate was ripe for a native composer to tap into those “fringe” elements that previous generations had discounted or ignored. While still a teenager, Villa-Lobos earned a living by performing in Rio’s thriving theatres and cinemas. And in 1905—though details are still debated—Villa-Lobos undertook a journey into Brazil’s unexplored interior in hopes of absorbing and transcribing the raw musical riches nurtured among the indigenous tribes. He did eventually marry and settle down to a long, productive career as a professional composer. But those early impressions came together to form Villa-Lobos’ mature style. Framed by a heady dose of incipient nationalism, it merges the exotic allure of Amazonian folk music with the vibrant “after hours” street culture. That scene included the chorőes, a form of strolling serenade that Villa-Lobos was to incorporate years later into fourteen pieces for varying ensembles.

Chôro No. 5, subtitled Alma Brasileira (Brazilian Soul), is noteworthy for the languorous pathos and infectious, subtle syncopations of its main theme, which encompasses a contrasting march-like middle section. The piece was written in 1925 in Paris, where Villa-Lobos had established himself as both composer and conductor. Frenchman Darius Milhaud had recently achieved great success with Brazilian-inspired works, and the fortunate Villa-Lobos came onto the Parisian scene just as France renewed her fetish for all things exotic. In fact, it was Villa-Lobos who personally introduced Milhaud to native Brazilian music when the latter traveled to South America in 1917. The basic elements of Alma Brasileira abound in many of his shorter piano works, such as Terezinha de Jesus and Senhora Dona Sancha, both of which encapsulate syncopated, dynamic middle sections between more lyric outer sections. From the same collection, A Condessa shows greater sophistication. Written in Rio in 1926, the piece’s principal melody works constantly to offset the troubling lowered-6-to-5 motion in an inner voice. That small gesture motivates greater chromaticism throughout the later portions of the short piece. And the brilliant O Polichinelo (1918) pays an obvious debt to Stravinsky’s Petrushka, where the juxtaposition of tritone-related sonorities first exerted its powerful influence.

Villa-Lobos’ later works, such as the powerful Ciclo Brasileiro (Brazilian Cycle, 1936), show an increasing preoccupation with foreign, even antique influences. Of course, indigenous elements survive; witness the serpentine first theme of the Ciclo’s second movement or the tribal rhythms of the fourth. But now they are wedded to piano textures derived from French and, especially, Russian traditions. Debussy’s spirit hovers over the first movement, in which shimmering bell-like ostinatos ring out above a baritone melodic line. The massive chords of the middle movements reinforce Villa-Lobos’ reputation as a “Latin Rachmaninoff,” though the third movement quotes more directly from the Shrovetide Fair portion of Stravinsky’s Petrushka. In the finale, native indian dance rhythms compete with echoes of the medieval dies irae plainchant, brought to South America by Jesuit missionaries but which Villa-Lobos likely absorbed from Rachmaninoff (who treated the chant as a personal leitmotif).

At a time when the avant-garde held sway, Villa-Lobos did not shy away from traditionalism. Yet he delved more deeply into the Amazon’s folk music interior than any other musician of international stature. An excellent example of these competing ambitions is his Guia Prático, a multivolume attempt to reinvent Brazil’s musical education through folksong. The pieces recorded here, all from Book 6 of the Guia Prático (1932), clock in at a minute-and-a-half or less and clearly echo Schumann and Tchaikovsky—both of whom composed albums for children. From the reverie of “The Little Dove Flew Away” (track 9) to the oompah striding of “The Crab” (track 8), these works typify Villa-Lobos’ pedagogical interest; they are heartfelt, colorful, but not technically demanding. For bridging the gap between rainforest and concert stage, between the erudite and the popular, he will forever be a pivotal voice in modern music and a Brazilian national treasure.

The life of Chiquinha Gonzaga (1847-1935) spans an era of dramatic changes in Brazil. Her experiences in particular demonstrate the highs and lows that women faced during the last days of colonial rule in South America. Gonzaga was fortunate at birth to be recognized and accepted by her white, affluent father; her mother being a mulatto, this recognition was hardly a small matter. With her father’s support, Chiquinha received an outstanding musical education focused primarily on the piano. Music would continue to offer solace in a life fraught with struggle and loss. A first arranged marriage ended in divorce; and with all laws favoring the husband, Gonzaga had to leave behind several children in the separation. A second marriage also faltered, and at age 30 she returned to Rio to begin her musical career in earnest. At first, Gonzaga languished due to outright chauvinism in male-dominated professional circles. Not to be deterred, she found success in the gritty theater world that Villa-Lobos, too, would one day patronize. Through it all she continued to compose everything from solo piano improvisations to light opera. Gonzaga’s beloved song Lua Branca presents a deeply felt romance, filled with pathos and yearning. Using the simplest possible form (one section repeated), Lua Branca isolates certain motives, including a fixation on the dominant note and use of harmonic minor scale, to create a palpable sense of anguish. By contrast, both Corta-Jaca and Annita inhabit a more vivacious realm. The latter makes no grand pretensions, merely typifying a popular music style of the later 19th century. Corta-Jaca is Gonzaga’s most famous tune, and it debuted as part of a larger burlesque show in 1895. The main theme could be slowed down and make a perfect bossa, though one revels in the up-tempo ragtime elements of the B section. Altogether, this is ideal parlor music, and its popular consumption by middle-class Brazilians helped insure Gonzaga’s long and successful career. Behind this good-natured façade stands a brilliant composer who broke countless gender barriers in the conservative culture of her homeland.

Ernesto Nazareth (1863-1934) belongs to a slightly younger generation than Gonzaga; in turn he was a strong influence upon the next generation, including Villa-Lobos. Like both of those composer/performers, Nazareth thrived at the boundary between classical art music and popular trends circulating around Rio. He never fully embraced the latter, however, and one continually senses his desire to become the “Brazilian Chopin.” But the lure of employment in Rio’s cafes and music halls could not be resisted. Dominated by piano music, Nazareth’s oeuvre contains 80+ tangos that rub shoulders with Chopinesque waltzes, polkas, and other dances. One of those tangos, Odeon (1910), demonstrates his easy brilliance in the genre: it is charming, harmonically interesting, and its percussive Trio section closes with subtle hints of ragtime. Often Nazareth himself or other musicians added lyrics to his instrumental creations. Thus the famous Brejeiro (ca. 1893) enjoyed international fame as a song for voice and guitar, and its distinctive rhythm and thematic shape seem to have inspired Milhaud’s Le boeuf sur le toit. Apanhei-Te, Cavaquinho refers to a choro style of improvisatory play, in which each musician tries to outdo the others in sheer daring and display. Nazareth stages the entire catch-as-catch-can in the piano’s highest register. Cavaquinho serves to remind us that such music often feels more at home in the spontaneous, creative milieu of the nightclub.

Oscar Lorenzo Fernández (1897-1948) was born and raised in Rio to Spanish parents who intended their son to a career in medicine. However, Oscar’s youthful penchant for music gradually took stronger hold, and he earned a coveted place at the Instituto Nacional de Musica under Francisco Braga and Frederico Nascimento. Though also touched by Brazil’s powerful indigenous music, Fernández’s temperament kept him more closely allied with the European tradition than many others of his generation. Succeeding Nascimento as a professor of harmony at the Instituto, Fernández eventually opened his own school—the Brazil Conservatory of Music—in 1936 and was its director until his death twelve years later. The Suite Brasileira No. 2, three contrasting movements on original themes, remains one of Fernández’s most popular scores. Opening with Ponteio (Prelude), the composer strikes a simple mood redolent of Schumann and Mendelssohn, particularly the latter’s Songs without Words. It’s well written if entirely conventional, and even the unresolved 7th chord at the close has its precedent in Chopin. The following song, Moda, improves on the lyricism hinted at in Ponteio. A short introduction leads into a more fervent episode, again echoing Chopin (specifically the Fourth Ballade) in a rush of chromatic parallel 6ths. Fortunately, the closing dance Cateretê strikes a completely new mood, and the movement is the highlight of the set. Tuneful without being trite, Cateretê captivates from start to finish with an invigorating rhythmic pulse that is relentless yet still delightful.

In music, as in other aspects of its modern culture, Brazil encompasses an incredibly diverse, vibrant blend of influences. Some of those influences—notably through European exploration and subsequent African slave trade—were forced upon the native Amer-Indian traditions. And as much as we delight in the musical results of such intermixing, the harsh reality of that history lurks just below the surface that often seems jubilant and carefree. Contrasts in this music abound, and one finds cases of blatant imitation of European models alongside works that infuse much-needed local flavor. All four composers represented on this recording did their part to help Brazilian music shed its dependence on outside conventions. Without them, the subsequent history of South American music—and thus, all music after the global love affair with bossa nova—would be a pale reflection of its true self.

Program notes by Jason Stell

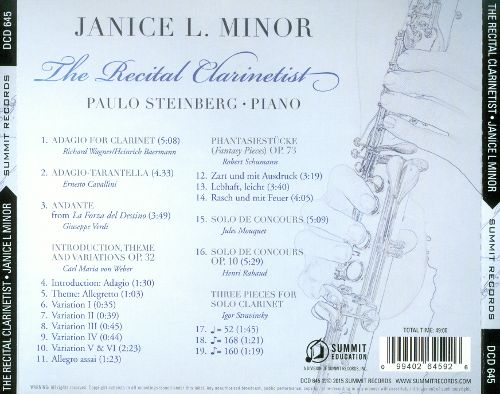

The CD-album The Recital Clarinetist, in collaboration with clarinetist Janice Minor, was released in 2015. Available on Amazon, iTunes, and Summit Records website.